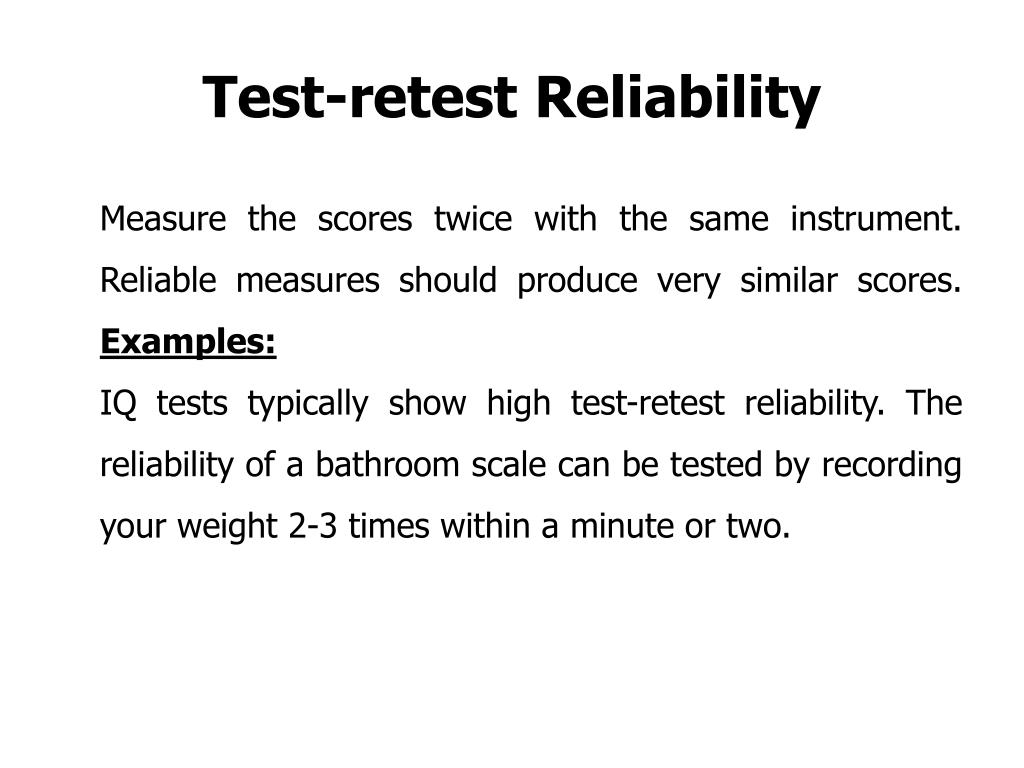

It wouldn’t be relevant for something like an organism’s weight. Note that test-retest reliability is only relevant for variables that do not change over time. If r is positive but weak, it is a sign of low test-retest reliability. If r is strong and positive (.05 or above), then you have good test-retest reliability. Test-retest reliability: Measure the same participants at least twice (Time 1 and Time 2) and then compute r. An r of 1.0 is the strongest positive relationship, an r of -1.0 is the strongest negative relationship, and an r of 0 or close to 0 is no relationship.ġ. The weaker the relationship, the closer r is to 0. The stronger the relationship, the closer r is to -1.0 or +1.0. When your slope is negative, r is negative r ranges from -1.0 to +1.0.

When your slope is positive, r is positive. When dots are spread out, you have a weak relationship. When dots are close to the line, you have a strong relationship. Which ones are positive? Which ones are negative? Which is zero? Strength: The spread of the dots in a scatterplot corresponds to the strength of the relationship. A and B show an upward slope from left to right (positive slope) C shows a downward slope (negative slope) and D does not slope either up or down (zero slope). Correlation coefficient (r): a single number that describes how close the dots on a scatterplot are to the line drawn through them Slope direction: Notice that the direction of the slope is different in the four scatterplots. However, it’s preferable that the three types of measures show similar patterns of results.Īlthough scatterplots are a good first step in evaluating reliability, a more common and more efficient way is to use the correlation coefficient. Which operationalization is best? A single construct can be operationalized in all three ways, and one way is not necessarily better than another. Physiological measures: operationalize a variable by recording biological data (e.g., brain activity, hormonal levels, heart rate) for example, operationalizing whether someone can distinguish between two different speech sounds by examining his or her brain responses to those speech sounds. Observational measures (aka behavioral measures): Operationalize a variable by recording observable behaviors for example, operationalizing allergies by observing how often someone sneezes, or using physical traces of behavior-as when operationalizing cleanliness by quantifying how much dust someone has on their furniture. Self-report measures: Operationalize a variable by recording people’s answers to questions about themselves in a questionnaire or interview for example, operationalizing caffeine consumption by asking, “How many caffeinated beverages have you consumed today?” Chapter 6 addresses when these are likely to be accurate and where they might be biased 2.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)